Protein distribution: beneficial, detrimental, or inconsequential?

The concept of protein distribution suggests that how you distribute your meals throughout a 24-hour period strongly impacts your overall anabolism.

There are contrasting lines of thought of what meal frequency is preferred.

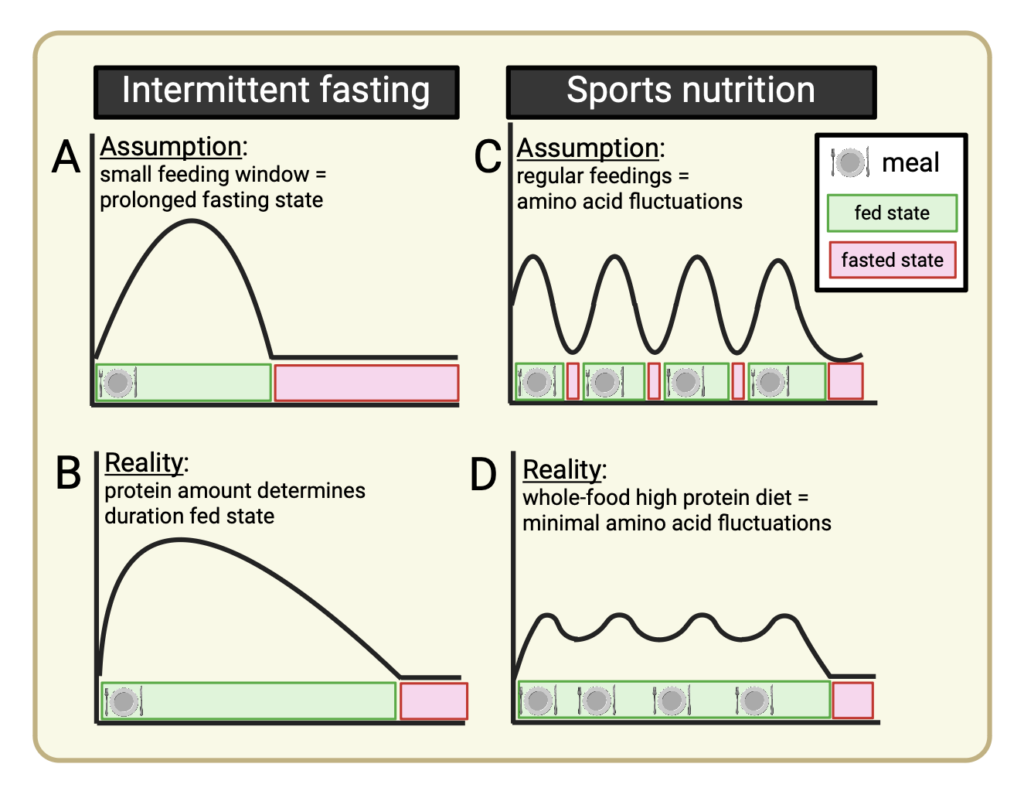

In intermittent fasting or time-restricted feeding, food is consumed in a relatively short feeding window. By not eating for most of the day, the goal is to be in a fasted/catabolic state, which is believed to be healthy. For example, it is thought to speed up the removal of damaged proteins (autophagy).

However, not eating does not equal being in a fasted state. If you have a lot of protein in your feeding window, that protein can still be digested for a long time, depending on the amount and type of protein in your last meal (> 12 h). In other words, not eating for 12 hours does not necessarily mean you have spent any time in a fasted state.

In sports nutrition, the opposite strategy is applied: eat multiple meals spread out over the day to optimize anabolism. The main thought here is that the anabolic response to a meal is only short-lived (although our recent work STRONGLY challenges this).

In practice, most protein is consumed as whole-food mixed meals that are slowly digested and will sustain high levels of plasma amino acids and anabolism throughout the day, regardless of meal frequency. Therefore, the amount of time spent with elevated amino acid levels and in an anabolic state likely has a lot more to do with the amount and type of protein consumed than meal frequency.

While there is some evidence that protein distribution may impact anabolism, the majority does not support it. In fact, even with intermittent fasting, there is no clear detrimental impact on muscle loss. Intermittent fasting represents an extreme model of supposedly poor protein distribution. Thus if you don’t observe an effect with such an extreme model, it seems silly to argue about 4 vs 5 meals a day for example. Therefore, protein distribution appears to have little to no practical impact on muscle mass in practice.

This is fascinating work, and if it holds true, it will change what we advise athletes regarding protein intake – it will be a real game changer! As you have highlighted, the current wisdom is to encourage athletes (especially those in strength based sports) to consume regular boluses of protein to maximise training adaptations and/or recovery. But you (and Kim et al Clin Nutr. 2018 on their work with older adults) are suggesting that a simpler approach i.e. a couple of meals with adequate protein are likely to achieve the same objectives as frequent meals that include post exercise and pre bed protein boluses. Have I understood correctly? Perhaps these findings explain why people were always able to develop incredible strength even in antiquity when it was unlikely that strong men had access to frequent protein meals?